Morisot

Berthe

Bourges 1841 — Paris 1895

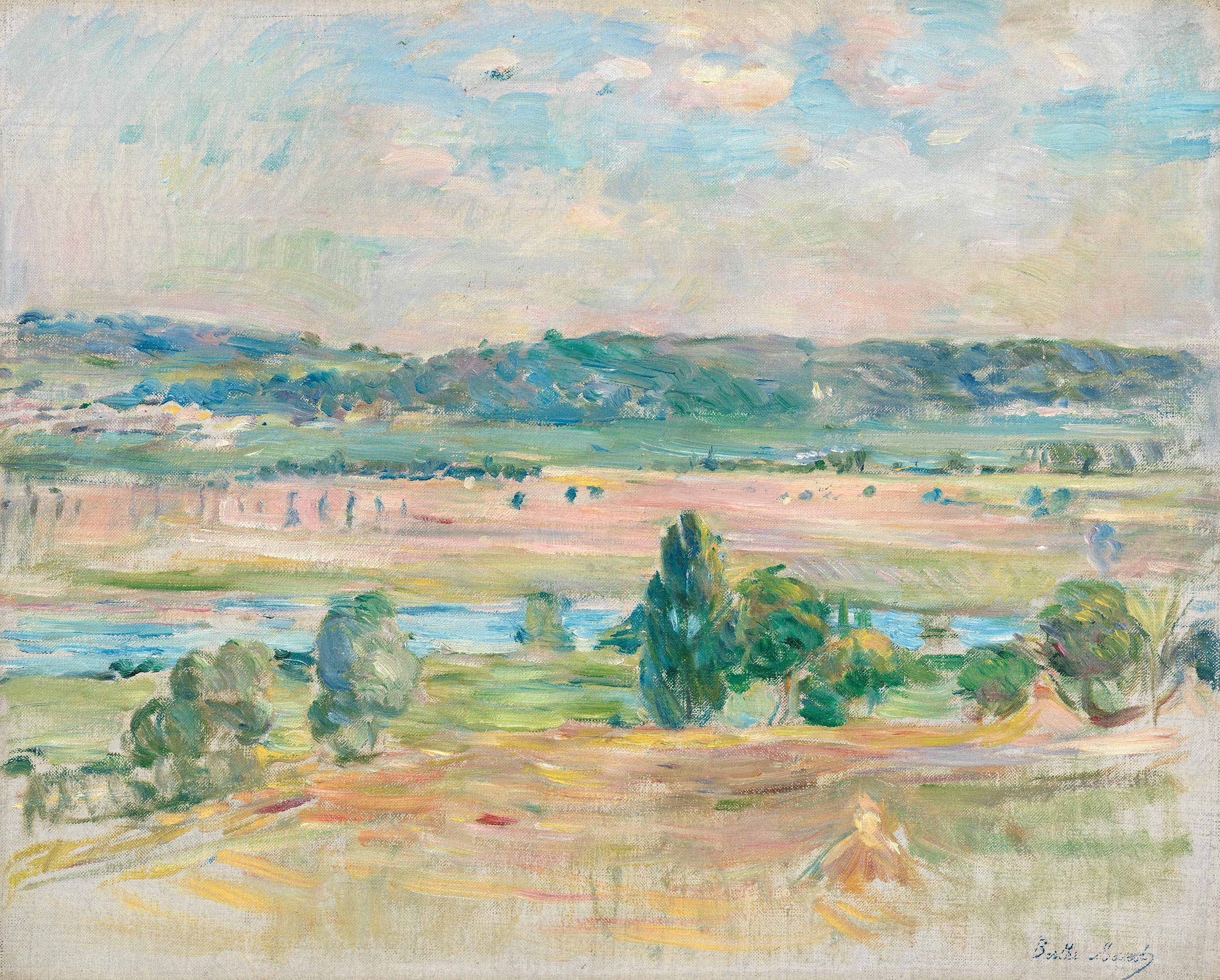

View of the River Seine

from Mézy-sur-Seine

Oil on canvas.

Stamp Berthe Morisot lower right.

33 x 41 cm (13 x 16 1/8 in.)

M. Ernest Rouart, Paris; Paul Brame, Paris; M. André Bauer, Geneva (acquired from the later on 21 July 1949); private collection (by descent).

Paris, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Berthe Morisot, 1929, N° 97 (lent by M. Rouart); Paris, Musée de l’Orangerie, Berthe Morisot, 1941, N° 88; Albi, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, Exposition Berthe Morisot, 1 July – 15 September 1958, N° 49 (lent by M. Bauer).

M. Angoulvent, Berthe Morisot, Paris, 1933, p. 138, N° 402 ;

M-L. Bataille & G. Wildenstein, Berthe Morisot. Catalogue des peintures, pastels et aquarelles, Paris, 1961, p. 40, N° 259 (fig. 262);

A. Clairet, D. Montalant & Y. Rouart, Berthe Morisot 1841 – 1895. Catalogue Raisonné de l’œuvre peint, 1997, p. 244, N° 263 (ill.).

Through the eight Impressionist exhibitions held between 1873 and 1886, Berthe Morisot has established herself among her peers as one of their own, considered by critics to be one of those “alienated”, as the critics referred to them. Alongside Caillebotte, Degas, Pissarro, Monet, Sisley etc., she exhibited works that rejected the academic tradition, great subjects, mythology, history and heroes, concentrating instead on everyday life, landscapes, simple people, the street, colorful sensations and a whole new apprehension of reality. Initially the only woman in the group, she was joined by Marie Bracquemond and Mary Cassatt at the fourth Impressionist exhibition in 1879. Her interest in feminine subjects, maternity, childhood and domesticity did not prevent her from receiving the recognition she deserved from her painter friends, including Manet, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Puvis de Chavannes and others. Renoir, for example, confessed to the art dealer Durand-Ruel: “Monet, Sisley, Morisot, they’re pure art.”

At the end of the 1880s, Berthe entered a new period in her life; the death of Édouard Manet had greatly affected her, as had that of Eva Gonzalès, for a time her rival; the illness of her husband Eugène Manet worried her. He had to spare himself and, in the spring of 1890, after a year spent in Cimiez near Nice, Berthe Morisot rented the Villa Blotière in Mézy-sur- Seine, northwest of Paris between Meulan and Mantes, where the garden offered a beautiful view of the Seine and where she had a studio set up. Although less prolific than usual, at Mézy she produced studies for large-scale paintings such as Saint John the Baptist Standing with his Cross, a lost work for which sketches survive1, and The Cherry Tree, which required a great deal of work and multiple sketches. She also painted pure landscapes, such as ours or the one in the San Diego Museum (California)2, very close (Fig. 1). She missed her friends; Monet was unable to visit her, but Mallarmé and Renoir came to spend a few days with her. With Mary Cassatt, who was staying in nearby Septeuil, they spent a day visiting the Japanese art exhibition at the École des Beaux-arts3. Not far from Mézy-sur- Seine, in Juziers, Berthe and Eugène spotted the Château du Mesnil for sale, which they bought in 1891 with the dream that “Julie will enjoy it and populate it with her children” (letter to Louise Riesener). Julie’s dream of simple, domestic happiness came true, and she settled in Le Mesnil after the death of her parents

At Mézy-sur-Seine, Renoir and Morisot were happy to paint together. The landscape here, a view of the Seine perhaps from the garden, shows how Morisot fixes on canvas a lightness, a beauty, an innate joy, with no connection to the sad events in her life. Her palette is joyful and luminous, her brush light and elusive, the transparent material delicately placed on the canvas in reserve. It’s a pink, ethereal landscape that captures the poetic and eternal essence of a morning rising over the countryside. It is written that the artist later took up the composition in a drawing for a fan project4. Berthe Morisot surrounded herself with young girls, Mezy’s models (for example, Gabrielle Dufour, model for the Bergère couchée (Lying Sheperdhess) or Jeanne and Emma Bodeau), friends and cousins of her daughter Julie who, after her husband’s death, would brighten up her daily life, bringing her the joy, beauty and poetry she needed. Despite the artistic doubts and uncertainties that beset her – “as I grow older, painting seems to me more difficult and more useless” she wrote to her sister Edma – her painting now expresses total harmony and, with the acceptance of the unfinished, the ability to “fix something of what is passing”. The 1896 exhibition organized by Durand-Ruel on the first anniversary of her death was “a wonder”, “like a resurrection”, in Julie’s words. It highlighted the beauty of the light, the fluidity of his touch, “the enchantment, yes the everyday … the enthusiastic innateness of youth in the depths of the day”, as Mallarmé, her faithful friend, wrote in the introduction to the exhibition catalog – words perfectly suited to our landscape.

- Saint John, Cleveland Museum of Art, gift of Mrs Lewis B. Williams, 1975.83.

- San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, CA, Inv. 1964.117, gift of Mr and Mrs Norton S. Walbridge; oil on canvas; 27 x 39 cm, 1891.

- Marianne Delafond, Caroline Genet-Bodeville, Berthe Morisot ou l’audace raisonnée, Musée Marmottan – Claude Monet, Paris, 1997, catalogue d’exposition, p. 66 et p. 95 note 79.

- A. Clairet, D. Montalant & Y. Rouart, Berthe Morisot 1841 – 1895. Catalogue Raisonné de l’œuvre peint, 1997, p. 244, N° 263.