Cassas

Louis-François

Azay le Ferron 1756 — Versailles 1827

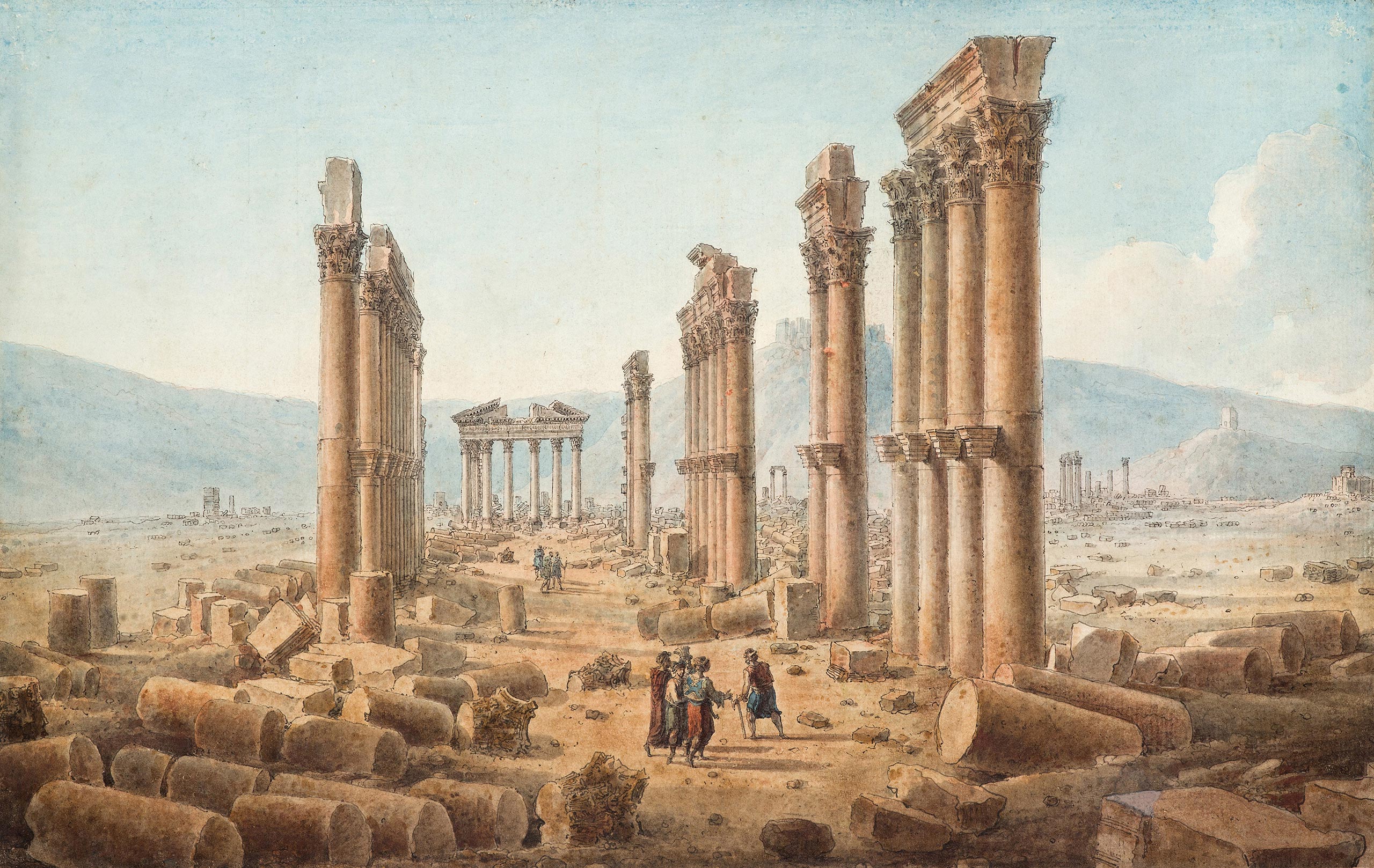

I. Temple of Neptune at Palmyra

II. Portion of the Great Gallery at Palmyra

III. Tombs near Palmyra

IV. Mausoleums near Palmyra

I. Temple of Neptune at Palmyra

II. Portion of the Great Gallery at Palmyra

III. Tombs near Palmyra

(Mausoleum of Elabelus and other funerary monuments)

IV. Mausoleums near Palmyra

(Mausoleum of Iamblichus and other funerary monuments)

Pen and brown ink, watercolour.

All four mounted in the same frame.

240 x 375 mm (9 1⁄2 x 14 3⁄4 in.) [drawing];

64 x 91.5 cm (25 1⁄5 x 36 in.) [frame]

The Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phénicie, de la Palestine et de la Basse-Égypte (A Picturesque Tour of Syria, Phoenicia, Palestine and Lower Egypt, 1799, 2 of 3 volumes, 330 plates) contains several plates related to our drawings.

- Our drawing corresponds to plate n° 87: Temple of Neptune at The view is taken from the north-west. The ruins of a large building are visible in the foreground. The same temple is engraved on plate n° 86 in reverse, observed from the south.

- Our drawing corresponds to plate n°81.

- Our drawing is engraved on plate n° 104: Mausoleums in the valley leading to Palmyra: this general view is taken near the tomb of Elabelus looking at the city ruins. The tower on the left, the mausoleum of Elabelus, is also studied separately on plates n° 119 and n° 124, and in details on plates n° 127 and n° 110.

- The engraving is not an exact reproduction of our drawing, but the view does correspond to plate n° 101: Mausoleums in the valley leading to Palmyra: this view is taken from the slope of the hill facing the desert. The mausoleum of Iamblichus is also studied in cross-section on plates n° 108 and n° 109 and in detail on plate n° 113. The composition is repeated in another work belonging to Musée de Tours, but on a larger scale with some differences.

The present watercolours in their orignal frame.

An intrepid traveller and tireless draughtsman, Cassas benefited from an education that was both eclectic and elitist. At the age of 14, his father, an architectural engineer, introduced him to the bridge worksite run by Cadet de Limay in Tours, who in turn introduced him to his future father-in-law, the Orléans amateur Aignan-Thomas Desfriches (1715-1800). Desfriches, a former pupil of Natoire who was close to all the leading artists of the time, introduced Cassas to Louis Antoine de Chabot who became the Duc de Rohan-Chabot in 1791, and his wife, Élisabeth Louise de la Rochefoucauld. They invited the young artist to participate in soirées at their private drawing academy, a place of artistic and social emulation where, between 1775 and 1778, he was able to meet the period’s most important figures. After a first trip to Holland in 1776, followed by a stay in Brittany, Cassas completed his training in Italy between 1778 and 1783 in the best possible manner: he accompanied his first patron, Louis Antoine de Chabot, and his family, drawing and producing hundreds of sheets, site views, landscapes and surveys of antiques, etc.; he selected rare items, antiquities, objects and paintings for his patron and expanded his network of friends and sponsors; he visited Milan, Parma, Rome, Naples and Venice, as well as Istria and Dalmatia (modern-day Croatia and a small part of Montenegro and Herzegovina), where he drew extensively. Finally, he ended his Italian tour in Sicily where he accompanied Vivant Denon to help illustrate Voyage pittoresque ou description des Royaumes de Naples et de Sicile (Picturesque Tour or Description of the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, 1781-1786, 4 vols.) published by the Abbé de Saint-Non.

After a brief return to Paris, in 1784, Cassas embarked on a journey that would take him to the Ottoman Empire’s greatest sites – Smyrna, Ephesus, Alexandrette, Aleppo, Palmyra, Baalbek etc., crossing through Egypt, Palestine and Syria on the way – at the request of the Comte de Choiseul Gouffier (ambassador to Constantinople from 1784 to 1791). He took the initiative to push on to lands that were virtually unexplored at the time such as Palmyra,1 which he only reached after great difficulty whilst “in constant danger of losing his life,” as he wrote to Choiseul Gouffier on the 21st July 1785. But “one suddenly discovers the most extraordinary and romantic sight: superb ruins, countless colonnades and porticoes, all of white marble, infinite remains of temples, etc… For two leagues, the land is covered with broken columns, capitals, statues, altars, etc… In the middle, the Sun Temple, the most beautiful and largest of all the temples of Antiquity, rises up and dominates the desert, which resembles a vast sea. It was within the walls of this beautiful monument that I was housed, and it was in the midst of the greatest dangers that I managed to draw and measure all that was of interest there.”2

The surveys Cassas carried out at the time, including the 200 or so drawings he made of the Palmyra site together with his written notes, are now crucial to our knowledge of these places, even if he didn’t always respect the topography in some of his reconstructed views. His drawings were eagerly awaited in Constantinople where his return to the city caused a sensation: “There’s something new here for architecture,” wrote a passionate stranger to the engraver Foucherot3. After nine months in Constantinople, Cassas returned to Rome where he stayed from 1787 to 1791, detained by several affairs for Choiseul Gouffier. Finally, back in Paris in 1791, he was able to devote time to publishing the graphic material produced during his travels, as well as his copious, fascinating notes. Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phénicie, de la Palestine et de la Basse-Égypte (1799, 2 out of 3 volumes, 330 plates); Voyage pittoresque et historique de l’Istrie et de la Dalmatie (Picturesque Tour of Istria and Dalmatia, 1802, 69 plates) and Grandes vues pittoresques des principaux sites et monuments de la Grèce, de la Sicile, et des sept collines de Rome (Grand Picturesque Views of Principal Sites and Monuments in Greece, Siciliy and the Seven Hills of Rome, 1813) were published, albeit with difficulty. In Paris, Cassas aroused curiosity and admiration and was able to make a living from selling his drawings. In 1806, he opened a small museum in his rue de Seine flat, where he exhibited models of the monuments he had drawn during his long journey, a collection bought by the State in 1813. From 1816 onwards, he worked as a teacher at the Gobelins and produced large watercolors for amateurs, depicting the sites he saw or spectacular events that took place during his travels, using sketches made on the spot and presenting his views in different formats. For example, a drawing owned by Musée des Beaux- arts de Tours bearing the title Tours funéraires des tribus palmyréniennes (Funerary Towers of the Palmyrenian Tribes), dated 1821, takes up the composition of our fourth drawing, though with some differences.

Of the four views reunited together in this frame, three were engraved in Volume I of his major work, Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phénicie, de la Palestine et de la Basse-Égypte; the fourth view is also present, but observed from a different point of view (see related works). Cassas engraved many details of monuments, interiors, cross-sections and ornaments too. He aspired to restore history’s reality: Palmyra is “the daughter of the desert,” he wrote in his Voyage pittoresque. In addition to the ruins, he wanted to show the desert’s aridity and the omnipresence of the sun, which is nothing more here than a “destructive tyrant”. “Everywhere in Palmyra, inside and outside its walls, sees a saddened land that is nowhere comforted by springs, grasses, plants or trees. Palmyra, the emulator, if not the example, of Rome, has never been able, like its happy rival, to combine its magnificence with freshness and shade.”4 These drawings are most likely part of the material assembled by the artist on site, drawn in pen and ink on the spot with later watercolor additions. The Victoria and Albert Museum possesses numerous works of a similar size and style – preparatory studies for the compositions in Voyage pittoresque et historique de l’Istrie et de la Dalmatie, compiled by J. Lavallée and published in two volumes in 1802. Executed in pen and wash in situ, they were also completed at a later stage with color introduced in the studio. This is probably the case for our works.

- In 1695, the account of two English merchants living in Aleppo who had reached Palmyra in 1691 was published in London; in 1751, James Dawkins and Robert Wood, accompanied by the Italian draughtsman Giovanni Baptista Borra, spent two weeks there and published their own account in 1753. These were the only explorations of the region before Cassas.

- Letter to Desfriches, 22nd January, 1786.

- Henri Boucher: “Louis-François Cassas”, Gazette des Beaux-arts, July-August 1926 (p. 27-53), p. 44, note 1.

- Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phénicie, de la Palestine et de la Basse- Égypte, p. 8.